MILOVAN FARRONATO: I have always thought that one of the Italian Lessons should be dedicated to clichés. In some ways, Italy lends itself superbly to this subject. Your on-going project Videogiochi, which you are presenting at Fiorucci Art Trust, also seems perfectly apt in this sense. What is a cliché for you? How and why can one emphasise (or vanquish) the already-stereotyped nature of an image?

ANNA FRANCESCHINI: I agree, to be Italian comes with a series of attributes that are easy to recognise – some of these being more flattering than others. Intuitively, when I think of a stereotype, a process of crystallisation comes to mind: a journey of gradual transformation whereby a custom loses its dynamic, gaseous form to become a fixed, solid body. Thus, for me a stereotype is inevitably linked to a zombification of characters, it’s a mask of death – a little bit like the characters from commedia dell’arte, or Plautus’ comedies. Mortuary figures relating to the ridicule.

Stereotypes are everywhere, they spare nothing. It is very easy to recognise a stereotype in other people – and generally this makes us smile – yet it is not as easy to accept it in ourselves. Take a commedia all’italiana film such as I Mostri (1963) by Dino Risi, where he stages some of the most terrible flaws of Italian society at the time. When we watch the film, we enjoy and laugh at this vicious portrait of society’s clichés precisely because we do not realise they belong to us too. We think, ‘Look at those monsters!’.

I think a way to ‘vanquish’ or overcome a stereotype is through a mechanism of explicit representation: isolating a kind of behaviour to then stage it and display it. This is a little bit what happens in our work with Videogiochi. Once the stereotype is acknowledged and we recognise it also as ‘ours’, our initial feeling of shame is quickly followed by laughter.

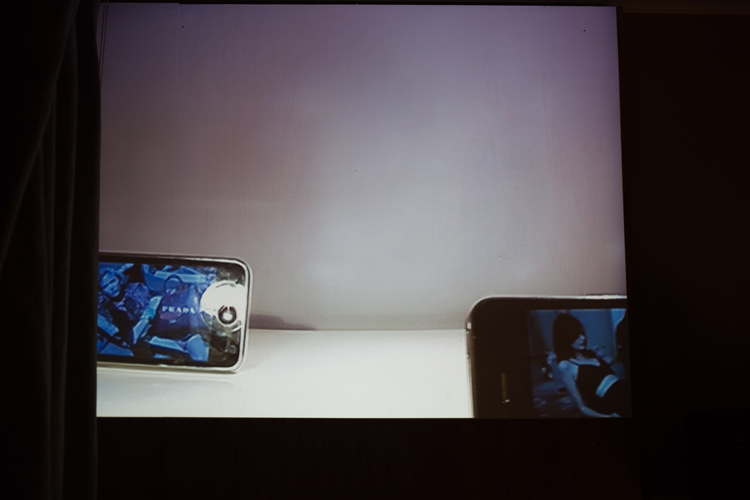

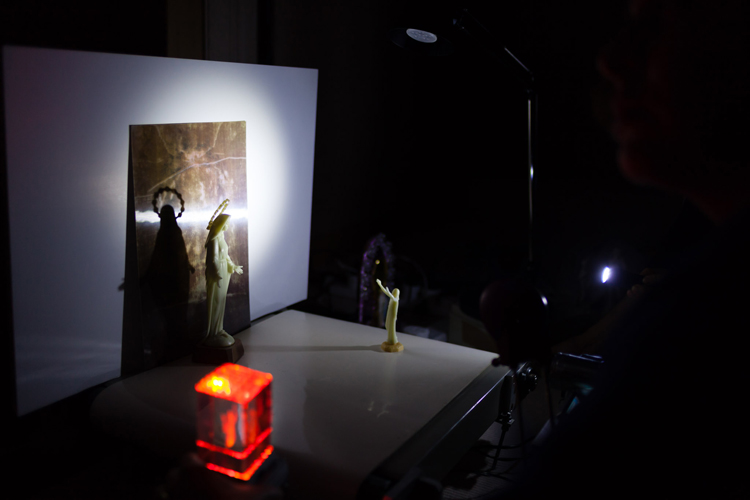

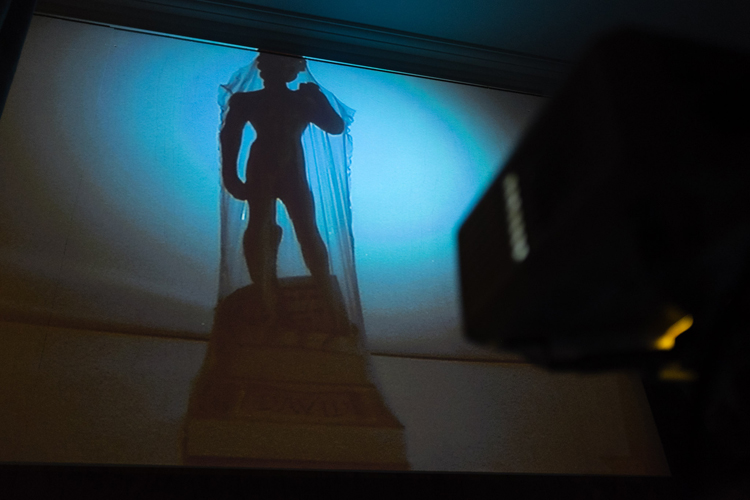

MF: Videogiochi includes a small theatre of unanimated objects, staged, filmed and projected live. It reminds me of one of Mike Kelley’s Harems – his dearest collections – but also of Joan Jonas’ performances where small props are filmed and projected live to build a narrative closely intertwined with music. How does Videogiochi relate to these references?

AF: Mike Kelley’s work on collections is very important to me. I got to know Kelley’s work a long time ago, through music rather than art, actually. His first work I saw was the cover he did for Sonic Youth’s album Dirty. I feel that what I might share most with Kelley is the attitude of getting attached to things, trinkets, trash that one might find in all sorts of places. I have an inclination towards accumulation, as well as the vernacular. Yet the outcome of this process is a feeling of profound disgust in front of the final ‘cumulus’ of stuff. I can’t even look at the objects employed in Videogiochi when I am not using them for the performance. Recently, Diego was also caught by a deep sense of nausea when, while looking for objects in Paris, he stumbled upon a large wall-display of maneki-neko!

MF: This is a question for you as well as for your collaborators on this project, artists Diego Marcon and Federico Chiari. Could you talk a bit about the process through which Videogiochi came together and how your individual skills enter in dialogue during the performance?

AF: Diego, Federico and I have been collaborating under the name pad/Piccolo Artigianato Digitale. Since the beginning, pad was not only a practise but also a manifesto to work collaboratively – this was not always easy. Many were there clashes and issues we had to face, which even brought us to separate after just one year. Videogiochi actually started back then.

DIEGO MARCON: The most difficult moment of the collaboration was when our roles seemed to have become fixed, when the trust between us had gradually become that of a professional, hierarchical contract. We were losing the complicity shared by artists who are collaborating on a project, while this is precisely how we connect now. My gaze is open towards Anna and Federico, and vice versa. We are aware that we are each other’s perfect pals for this game. It’s hard for me to think of myself and Anna as film directors. Even though our individual research takes different trajectories, I believe we share an approach where the primary instrument is the gaze. Federico is much more focused on a sensibility towards sound and the aural components of the project.

Videogiochi itself is a bizarre and mysterious context where we find ourselves sitting among trinkets, souvenirs and toys… the presence of these objects in front of our eyes activates for each of us a mechanism of curiosity, which is the very drive of the work.

FEDERICO CHIARI: I feel I had to develop a ‘mechanic ear’ to side the ‘mechanic eyes’ of Anna and Diego’s filmmaking practise. I feel it is true that we work equally, on the same level – all three of us are in charge of activating a device which has a non-life of its own, which requires some sort of distance on our part in order to work. As a musician, my main role is to interpret this very distance and expand it as much as possible.

Photography by Lewis Ronald