Volcano Extravaganza 2019 – Death // Epilogue

by Lavinia Filippi

Day 1 // 18 July

Day 2 // 19 July

Day 3 // 20 July

Day 4 // 21 July

Volcano Extravaganza 2019 - DEATH

Back

by Lavinia Filippi

Exactly twenty years ago, the year my father died, I spent a restless summer wandering in the Aeolian Islands. I was very young and did not know how to deal with this overwhelming event. The only condition that seemed bearable was that of transit, and therefore the archipelago appeared as the perfect configuration to grieve my loss. The repetitive aspect of my constant displacements between islands eased my suffering, as it reassured me that normality could eventually resume and life continue. At the same time every shift was transformative, it revealed something new, another vegetation, a different rock or simply an unexpected light effect. Stromboli was the last stage of my meditative pilgrimage. As soon as I disembarked I wrote a poem in which I described my father’s illness through the geological and aesthetics characteristic of the island. I was finally able to start a mourning process.

When Death was confirmed as the title of the recently concluded ninth edition of them Stromboli-based festival Volcano Extravaganza, it clearly made an impression on me, even though Artistic Leader Maria Loboda has always maintained that the theme should not be taken too personally and that ‘the idea of Death, is not only what is meant to be the biological end to life but as transforming end to what one knew until a very specific moment’. Death was inspired by the very nature of the site, which – as often recalled by the Fiorucci Art Trust’s Director Milovan Farronato – is at the same time an island, a mountain and a volcano whose energies are in precarious balance between benevolence and malevolence. Its landscapes are astonishing but its top constantly sputters smokes, ashes and vapours, and the possibility of reaching or leaving the island’s shores depends on the will of the elements. This condition forces you to think about the precariousness of human existence and, as in my adolescent experience, it drains you and spurs you all at once.

Volcano Extravaganza 2019 invited its participant artists to investigate the various possibilities that Death opened up by sharing a tale from the Babylonian Talmud on its inevitability, recovered by writer William Somerset Maugham in 1933 and best known as Appointment in Samarra. All of them had somehow already looked into certain aspects of this major existential quest, directly or transversally, as an isolated intimate event, a collective chronic condition or an aesthetic, physical, psychological inescapable component of life. This year’s festival, that unfolded through four days, was structured like a composite novel where each short story focused on a specific aspect of the overall narrative, while building up tension between interwoven sequences and highlighting converging thoughts or contrasting views. Like four independent chapters, that eventually lead to the identification of three recurring principles, each day had a title ironically inspired by legendary, eccentric, historical banquets, as well as a suggested dress code, which contributed to sense the mood and unleashed the imagination of those present. To quickly get acclimatised, the Fiorucci Art Trust’s guests also received, upon their arrival in Stromboli, what we called a ‘survival kit’: an enigmatic yet transparent bag containing a series of objects, carefully selected (sometimes even produced) by the participants, to help navigate the different phases of the journey.

| The three main statements expressed by the collective voice of the Volcano Extravaganza 2019 artists were: death as second possibility, death as endless repetition and search for relief, and death as the ultimate moment of truth. Although death as a second possibility might sound like a contradiction, a number of works selected or produced for this year’s festival, were somehow presenting death as a means of survival. This does not entail the traumatic, devastating side of it was not considered, but it is precisely from crisis that opportunities sometimes emerge. If we look at nature, where things are often more straightforward, meaningful and sensible, certain species pretend to die in order to continue to live. This fascinating anti-predator strategy, also known as thanatosis or ‘apparent death’, is a state characterised by cessation of all voluntary activity and assumption of a posture suggestive of death, in order to confuse the hunter. The same unique dead city of Pompeii, where the festival culminated, would not exist the way we know it today if it had not been destroyed and buried by the lava of the Vesuvius around 79 CE. The first event of the 2019 edition of Volcano Extravaganza, took place at sunset at La Lunatica. Guests were asked to dress according to the gospel of Live and let die and the title of the evening was Fête Worse Than Death, after the party organised in 1661 by Louis XIV’s finance minister, Nicolas Fouquet, which was deemed too ostentatious by the capricious French King. An ambiguous omen haunted our fête, one could sense it from the street where Malevolent Presences, performative concept by Maria, were frightening while inviting the attendees. In order to reach the terrace overlooking the sea, visitors had to pass through Vapore, an immersive mural, gouache and tempera over carbon tracings, by Nicholas Byrne. Inspired by the late medieval iconographic theme of the Danse Macabre, the work reminded everyone about the fragility of life, the futility of earthly glories and the universality of death. That said, it came with a dose of inexplicable joyfulness, after all the setup of most danse macabres is that of an afterlife party where skeletons and people from every walk of life dance together. |

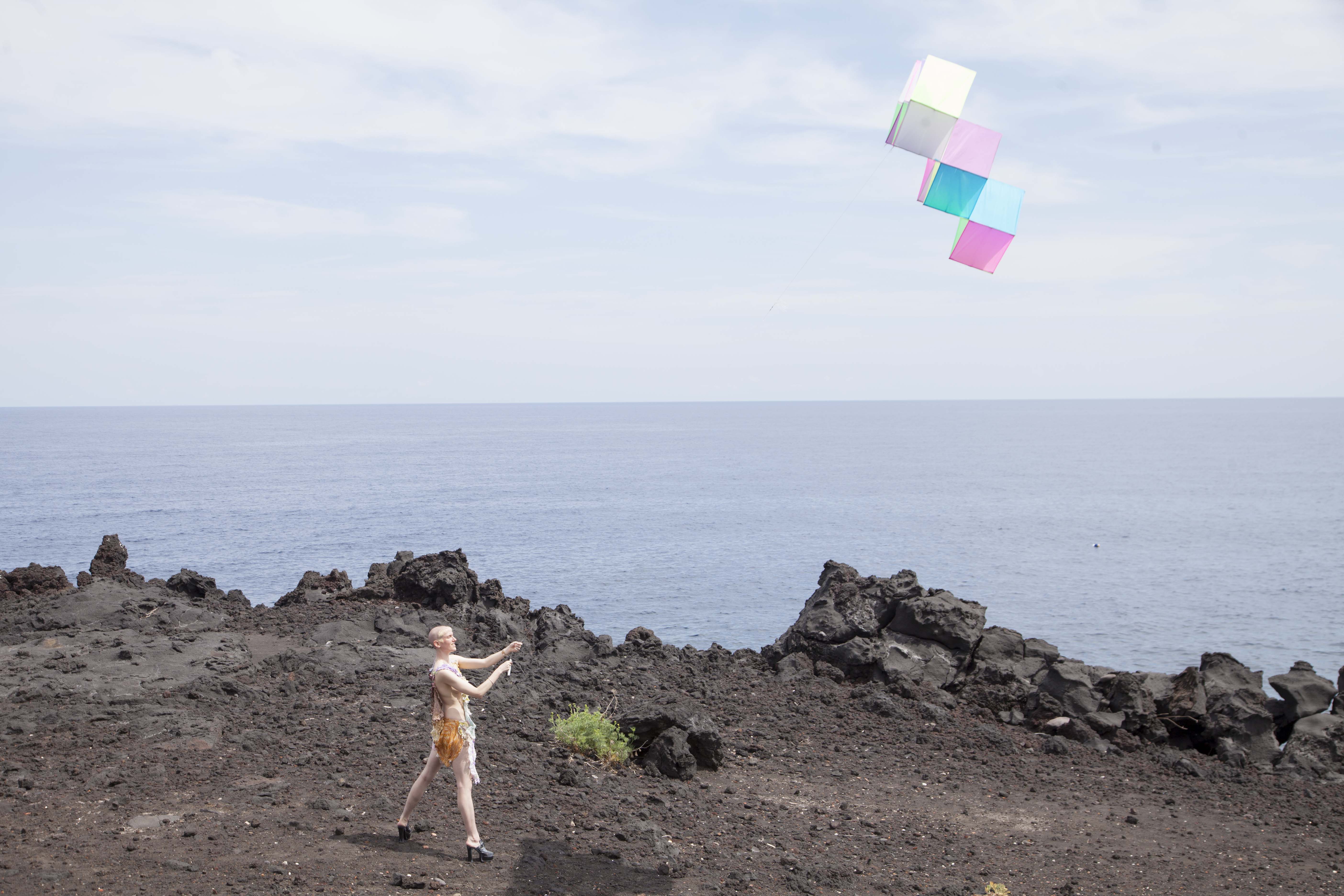

Outdoor, one side of the terrace was invaded by Borrowed Landscape with burial artefacts, an installation by Maria which included a cascade of big, round, volcanic stones from the cliff below, interspersed with cut-outs of enlarged images of precious treasures from different archaic cultures, given to the dead to keep them company and to enjoy in their afterlife. The possibility of an existential continuation was implied: a place, or a state, where all these artefacts – meticulously picked and gathered –might be once again of use. To celebrate the first day of the festival, a long table was set with fabrics especially designed and dyed locally by Agnieszka Brzeżańska, aligned with her oyster ghost sculptures, that reminded us of the destructive consequences of ocean acidification: a cry for help from a colony of victims that advocated for one more chance. Before the sun left its place to the moon, on the rocks towards the sea, Sorrow Part I, by Anthea Hamilton took shape. Despite the low wind, a rare situation on the islands that took their name from the king of winds, performer Eve Stainton – wearing a reinterpretation of Scrumbly Koldewyn’s ‘Doily Outfit’ (1972) by Alex Padfield – flew one of the kites interpreted and developed by fashion designer René Schienbenbauer. At that point Maria and Milovan had started inviting a few people to sit at the table, and become part of the stage, and served them the ‘discomfort food’ prepared by chef Jonas Palekas. The ambiguous balance between attraction and aversion, of beauty and inhospitality that also characterises Stromboli, combined with an impression of being part of the dress rehearsals, was further accentuated by Julie Béna’s performance, delivered in two acts. The first one where she jumped on top of the table in the middle of the dinner and the second by appearing from a window of the house overlooking the terrace, as a warning to encourage people to leave. The Jester songs, adapted and expanded on the occasion of the festival, were originally dedicated to malformed new-born creatures that Julie encountered in the anatomical wing of Palazzo Poggi museum in Bologna. Through her singing the artist wanted to make them live again, give them a second chance, whilst acknowledging their difficulties.

The second aspect that violently surfaced during the festival, primarily from the work of Albert Serra, was death as an endless repetition and search for relief, as a long-lasting agony and a desperate attempt to fulfil unappeasable desires. Like Iddu, ‘him’, as the islanders call in Sicilian dialect the volcano, that has been in constant activity for two thousand years, muttering and wriggling without being able to find peace. This characteristic of death, also raised by Prem Sahib in Cruising Pompeii, the performance he presented on the last day of the festival, might be physical, mental, metaphoric; it could be sudden or testify a slow, eternal, transformative decline. A condemnation with no way out, almost a curse, like the Appointment in Samarra story that has been told by many and heard by everyone at least once. The characters, as well as the locations, are changing from one version to another, but it always tells about the one appointment that cannot be missed. Whether the main characters were two Cushites in the Mesopotamian version, a young Persian gardener in Le grand écart (1923) by Jean Cocteau, or a servant in the play Sheppey (1933) by Maugham; with their point of arrival respectively the district of Luz, Isfahan or Samarra. They all travelled miles to encounter what they were trying to escape.

The initial atmosphere of the second day of the festival was the one recalled by the philosopher Federico Campagna in NONNULLA. Notes for a talk in Pompeii [1], of a playful ‘lazy Sunday afternoon’ where ‘time stretches eternally’ and things are not to be taken too seriously. Guests were coming and going, in the wild garden of Casa Monte, crossing over the woven straw gate by Agnieszka, lying down on the large communal picnic rugs she designed, chatting among Anthea’s giant white balloons and experiencing the participant’s interventions in a bucolic atmosphere. These included Trouble, a reading performed by Julie wearing a silk light pink négligée, sensually teasing, caressing, creating inappropriate, decontextualized moments of intimacy with the spectators. It also included Anthea’s performance Sorrow Part II, featuring Eve on the top of the small terrace overlooking the garden, creating a series of repetitive, pulsating, fast movements. Inside the house guests could try to alter their state of consciousness by watching with closed eyes Love spell, Maria’s Dream Machine, spinning around indeterminately. A softer though similar effect could be reached by playing with Psychedelia, a liquid-lights show equipped by the artistic leader the following day at Casa Carlotta during Feast of the Beast (dress code Sodom and Gomorrah).

As was to be expected, The Ultimate Orgy afternoon, with suggested dress code Divorce Me, Darling!, evolved into a feisty evening with the sheltered outdoor projection of fragments of Liberté (2019), introduced by Albert. The movie that won Un Certain Regard prize at Festival de Cannes, describes the uses and costumes of a series of high class, libertine characters, expelled from the puritanical court of Louis XIV, desperately and carelessly pursuing their quest for pleasure. The slow but inexorable crescendo of action returned the following day with the screening of Roi Soleil (2018)– an hour-long staging of the agony leading up to the monarch’s death – and with the following performance, for which Albert asked some of us to re-enact certain historical figures from ancient Greece and ancient Rome, in the last moments of their lives. Deyanira helped by her wet maid, Lollia Paulina supervised by a soldier, Cato the Younger, as well as Pherecydes of Syros assisted by one of his pupils, died for over an hour, perhaps physically and mentally exhausted by the consequences of extreme behaviours of the previous day, whereas the party was– once again – starting to take off thanks to Prem’s and Alec Curtis’ sounds.

The third predominant view identified by the collective voice of the Volcano Extravaganza 2019 participants is death as the ultimate moment of truth. For the final stage of the festival, like the servant in the tale, we all moved from Stromboli to Pompeii, dressed as A Satyr’s Choice, ready for The Dissolute Household, the event that ended with a last supper grounded in local flavours offered by Nicoletta Fiorucci, the founder of Fiorucci Art Trust and created by chef Emmanuel Di Liddo. Transits are an opportunity for reflection, to evaluate the outcomes of what you just left behind. It is a time for a showdown, and so is death. This moment of revelation was built up over the days of the festival by the Omnipresences, a series of figures modelled after plays, films, novels or previous performances, who discretely distracted, teased and kept us company throughout the journey. Inexplicable and unannounced presences in Stromboli, they revealed themselves for what they were in the mainland. Not only, were they performers tasked by Maria, but also characters that were going through an existential transformation. The bell boy that was going up and down the island in uniform carrying suitcases, appeared as the Satyr host of the Archaeological Park. Brick Pollitt from the Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) who was roaming around with crutches, drinking whisky and suffering, healed and cheered. The banker modelled after Gordon Gekko, the protagonist of Wall Street (1987), solved his connectivity problems, stopped being rude and danced, following the music of his new phone. The lovers tenderly flirting in Stromboli broke up in Pompeii, while the Marquise de Merteuil, who was silently breaking her pearl necklace, finally appeared as her serene self in a spectacular dress of her times.

Another opportunity to take stock of what had been, was offered by Lucas Arruda’s small seascapes paintings. Wisely scattered among the remains of Pompeian frescoes they seemed to have been always inside the Villa dei Misteri waiting for us.

Without evident beginning nor end was also Sorrow Part III, for which Anthea and Eve engaged in a series of improvised movements wearing the costumes originally created in collaboration with Jonathan Anderson for the Tate Britain show The Squash (2018). By respectfully moving through the ruins and becoming part of it, the performers contributed to highlighting their double nature as eternal and provisional. They also emphasized the relativity of time which could be, in Federico’s words ‘the only resource that holds life over the abyss’, and this is if there was nothing after death.

The work that concluded the ninth edition of the festival was Cruising Pompeii. In an outdoor courtyard of Villa dei Misteri eight young men performed a repetitive, enigmatic, almost non-perceptible choreography, guided by the sound of a motorbike in the distance and by the light of their phones. Like in a game or a ritual, the performers ultimately had to take a decision, make a choice and find their counterparts, before disappearing into the dark alleyways of the Archaeological Park. A sombre reflective surface, like the Obsidian Mirror, Prem’s traces of his latest travels to another volcanic island,which could be understood as an invitation to take a moment to check one’s appearance or take stock of one’s life achievements.

Death is without a doubt an end but it is also a beginning or a continuation, since, as concluded by Federico Campagna during his site-specific lecture: ‘before birth and after death there is not-nothing’. It is the commencement of something else, on which many throughout the centuries investigated. Science has been experimenting ways to postpone that moment or to experience ittemporarily. Philosophy has its raison d’être in it, since the analyses of the concept provided one of the main stimuli to the development of the discipline; while most religious beliefs offer options for the after-life – usually a better or a worse situation – trying to condition behaviours in the current one. What is certain is that death is both feared and challenged. As it emerged from the contributions of Volcano Extravaganza 2019, it is the ultimate moment of truth, often reached by searching endlessly for something, which nevertheless also considers the possibility of being given another chance.

Words by Lavinia Filippi

Photos by Daniele De Carolis