Artist’s Perfume Workshop at Creative Perfumers #1

The first in a series of perfume workshops curated by Fiorucci Art Trust in collaboration with Creative Perfumers, London.

16 May 2014

Creative Perfumers, 21 Arlington Street London SW1A 1RD

Back

The first in a series of perfume workshops curated by Fiorucci Art Trust in collaboration with Creative Perfumers, London.

16 May 2014

Creative Perfumers, 21 Arlington Street London SW1A 1RD

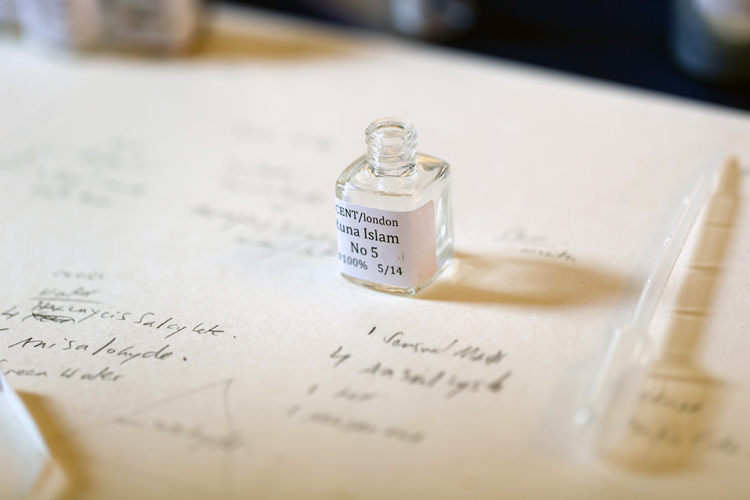

Participants: Stella Bottai, Patrizio Di Massimo, Lucas Dominguez, Milovan Farronato, Nicoletta Fiorucci, Charlie Fox, Beatrice Gibson, Celia Hempton, Runa Islam, Isaac Julien, Marie Ramsden, Magali Reus, Prem Sahib, Francesca Sarti, Paul Schutze, Osman Yousefzada.

Text by Charlie Fox

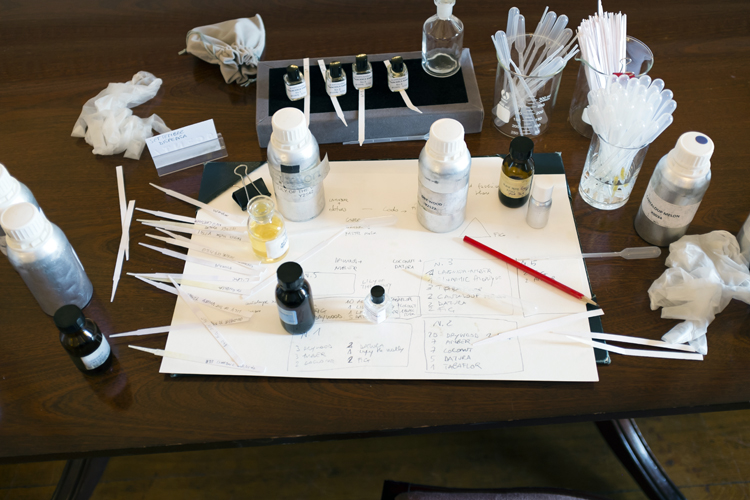

Photos by Lewis Ronald

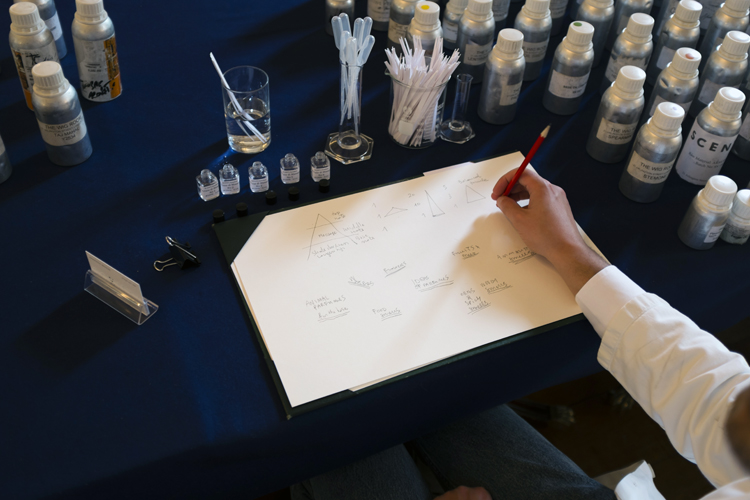

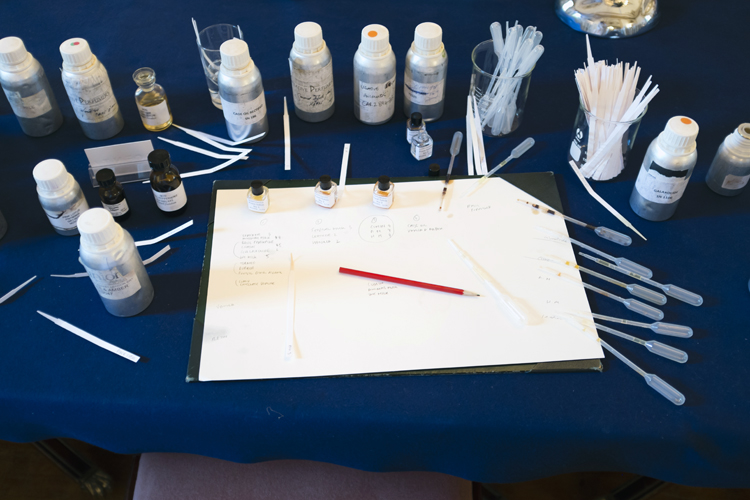

That afternoon, the perfumers told us about Juliet’s tomb. The sun was idly lighting the room, which was halfway between a laboratory and a banquet hall. There were hundreds of silver goblets on the table containing aesthetic chemicals and a painting of an opium smoker and an odalisque, half-awake, high on a far wall. I was the lone writer in the company of fourteen artists at the headquarters of Creative Perfumers.

In a recent collaboration with the Royal Ballet, they had invented scents for the dancers, costumes and interiors in a production of Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet. The gloomy chamber where the two lovers expire was carefully suffused with the faint stench of a gothic mist, moss-green in a little vial. (On a quick sniff, you detected the blind things hidden in the rotting bricks). The Montagues and the Capulets were scented like rival packs of dogs for their slow-motion fight in the first act. A cloud of poison lurked in the air even then, as everyone staggered away.

I don’t have any special knowledge of perfume. I sometimes wonder, in the vacant and dreamy way of a mid-morning drunk, about the scent of the white gardenias in Billie Holiday’s dressing-room, and the dark breath of her boxer dog Mister, or I dimly imagine what Delphine Seyrig’s treasured fragrance was in 1975 and end up instead recalling the lingering fumes from spent fireworks last October. (Each scent, on careful examination, would identify a different kind of desire). But perfume is a hallucinatory medium, a certain susceptibility to dreams, to odd wolf-whistles and sighs of desire might be more valuable than some recondite knowledge.

I spent the afternoon hallucinating as the perfumes led me in and out of distant rooms and coloured fogs, dreams and subsumed memories. Huffing so many so quickly sent a weird silvery glitter dancing through my head, akin to the effect of some impossibly high-grade amyl nitrate. Adumbrating the sensual flight induced by a fine perfume is its own outlandish, brutal art. My blurry daydreams grew stranger and more vivid with every additional inhalation, my mind looping a line from one of Lorca’s poems: ‘No one understood the perfume ever’.[1] Words feel weak against the flood.

But there is the weird poetry of the scents themselves, all named, numbered and carefully arranged, the exquisite fetishism of the pharmacist’s cabinet sprawling around the room: ‘Actophenon’, ‘Tree Musk Absolute’, ‘Cotton World’, ‘Epicene Gamma’, ‘Horse Extreme 2’, ‘Ange D’ Amour’… A jungle of meaning is hidden inside that little list: each name is a curiosity, hinting at a certain kind of world- I fell hard for the woozy, medicinal allure of ‘Cotton World’- a particular kind of seduction, glamour or a hit of pure strangeness. (‘Epicene Gamma was infinitely odder than ‘Horse Extreme 2’). The attraction is that they remain unreadable, just flashes of a certain sensation. There were no maps and even if they appeared they wouldn’t remove the mystery.

The underlying conceptual enticement of the afternoon was that perfume might be something other than a glamorous mirage and transform with the correct attention from a largely forsaken artistic element into a seductive undercurrent or spooky counterpart to a piece of work.

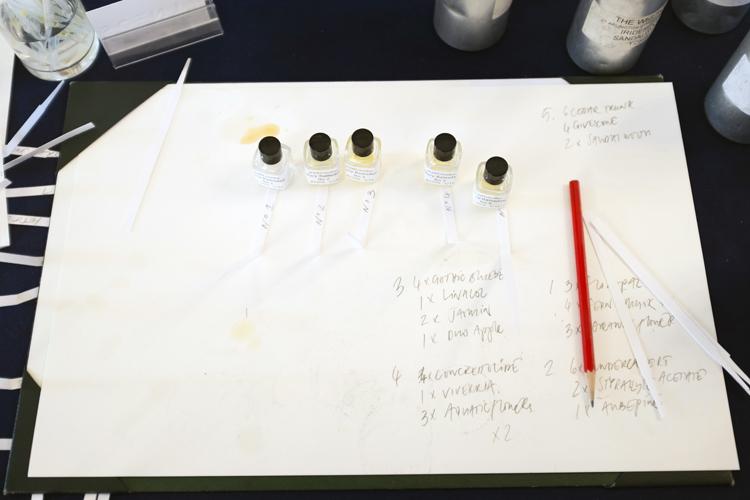

The sprawling assortment of artists came from many disciplines and included painters, filmmakers, a musician and a fashion designer. They had to invent their perfumes to explore what this peculiar science might produce and make meaning out of thin air. Some of the artists worked in silence, some pursued irregular questions. Issac Julien worked at the head of the table sitting in a curious wooden throne. Beatrice Gibson told me she was making greed into a perfume for a character in her next film: ‘like spring but sinister’, she said. Paul Schutze, long fascinated by perfume, tested multiple scents on pieces of paper which spread across his table in a gloomy peacock’s fan.

My first attempt was marked by willful perversity. I wanted to be ugly and conjure the dying breath of a bachelor so took tobacco for my base note- the fragrance’s suggestive undercurrent- which came from a bottle caked in brown grime, added tea traces, autumn damp and something that was discreet but so caustic it probably came from an abandoned factory. I experimented (and accomplished nothing) with ‘Melysflor’, a disconcerting educational scent of synthetic pine and empty corridors which removed all thought from my skull. Later I tried to add the flutter of a bird, or what my memory told me was the scent of a dead bird’s bluish feather found once on the ground.

Four hours later, I was in possession of five faintly green, drowsy perfumes. My muse was a Polaroid-fuzzy mind’s eye image of an actress, probably Nastassja Kinski in Paris, Texas, slinking through a forest. That spooky snapshot, which emerged from nowhere and returned there erratically all afternoon, is my own symbol of perfume-making’s full erotic and conceptual strangeness: a carnal and yet deeply melancholy art, an alchemy that tries to conjure ghosts.

Familiarity with hopeless longing is probably useful for the perfumer, who spends so long in pursuit of certain memories, carried on their phantom breeze. Experimental reverie has to be followed with a very delicate kind of attention because you’re tracing something hazy but deeply allusive which is always on the cusp of some new, ingenious escape. (For the artist, naturally, echoes abound: whatever you wish to make always has this feinting, Cheshire Cat presence).

A line from Nabokov’s Lolita: ‘The scent I travelled upon was so slight as to be indistinguishable from a madman’s fancy’. Things came into focus just as someone mumbled the occult words: ‘Nothing is singing!’

[1] Federico Garcia Lorca, ‘Ghazal of Love Unforeseen’ (c. 1931-34) , Selected Poems (Penguin, 1997)